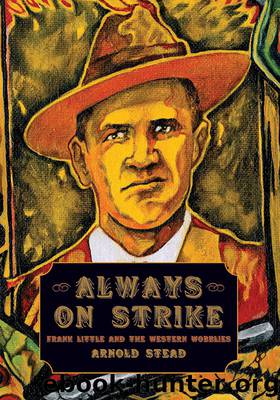

Always on Strike by Arnold Stead

Author:Arnold Stead [Stead, Arnold]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: Biography, History

ISBN: 978-1-60846-226-1

Publisher: Haymarket Books

Published: 2015-04-07T23:00:00+00:00

Agricultural Workers Organization (AWO)

Between 1913 and 1916, the emerging AWO pumped new life and money into the IWW and brought the Mesabi Range as well as the surrounding farm country in Minnesota, Wisconsin, and the Dakotas under the union’s close scrutiny. Of course harvest work, performed almost entirely by migrant laborers, extended far beyond those four states. In his Harvest Wobblies, Greg Hall writes that in Southern California, the Plains states, and the Corn Belt, Wobbly organizers known as job delegates “signed up men in the field while working along with them.” The working conditions of these men, women, and children closely resembled those documented by Carleton Parker at Wheatland. Being forced to live on wages from $1.00 to $2.50 for ten-hour workdays kept these laborers constantly on the move looking for their next job. The AWO gave them a strength they had not before known. The union organized strikes for better pay, shorter working hours, and better living conditions. These strikes were usually victorious since the farmer was under pressure exerted by nature to get his crop picked or lose money.

The job delegate system, while defended as the best method of keeping the IWW in the hands of the workers rather than the Chicago leadership, had a tendency to put too much focus on the hobo jungles. The strategy reached more men than on-the-job organizing, but it also resulted in nonunion workers being hired, thereby leaving the IWW with no leverage at the workplace itself. It may well be the jungles’ effectiveness as recruiting sites for the free-speech fights that caused organizers, Frank Little among them, to overestimate their value for union organizing.

Little’s suggestion at the ninth annual IWW convention in 1914 brought about the formation of a Bureau of Migratory Workers. Its mission was “to set up the conference, coordinate information on jobs, and further organization among harvest workers.” In October, Solidarity reported that the bureau was working “to combat ‘the schemes of labor bureaus and employment sharks’ whose exaggerated accounts of labor shortages produced a surplus of labor, driving down wages and forcing many unemployed harvest hands to resort to begging and stealing.”

On April 21, 1915, a conference to discuss how best to organize harvesters took place in Kansas City and drew representatives from Des Moines, Fresno, Minneapolis, Portland, Kansas City, Salt Lake City, and San Francisco. A pal of his, E. F. Doree, a tirelessly active AWO leader, may have been Little’s source of insider information at the conference.4

After voting against the use of street speaking as a “means of propaganda,” the delegates established the Agricultural Workers Organization 400. The new organization’s agitation committee put forth a list of demands for the 1915 harvest season, which included “minimum wage of $3.00 for more than ten hours a day; 50 cents overtime for every hour worked above ten in one day; good clean board; good clean places to sleep in, and plenty of clean bedding; and no discrimination against members of the IWW.” A notice in the

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Arms Control | Diplomacy |

| Security | Trades & Tariffs |

| Treaties | African |

| Asian | Australian & Oceanian |

| Canadian | Caribbean & Latin American |

| European | Middle Eastern |

| Russian & Former Soviet Union |

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(18998)

The Social Justice Warrior Handbook by Lisa De Pasquale(12177)

Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher(8873)

This Is How You Lose Her by Junot Diaz(6855)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6248)

Zero to One by Peter Thiel(5762)

Beartown by Fredrik Backman(5708)

The Myth of the Strong Leader by Archie Brown(5480)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5409)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(5200)

Promise Me, Dad by Joe Biden(5128)

Stone's Rules by Roger Stone(5065)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4937)

100 Deadly Skills by Clint Emerson(4898)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4757)

Secrecy World by Jake Bernstein(4727)

The David Icke Guide to the Global Conspiracy (and how to end it) by David Icke(4683)

The Farm by Tom Rob Smith(4484)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4473)